More than a dozen political prisoners, activists, and members of the opposition in Azerbaijan have joined a solidarity hunger strike to call attention to the plight of the imprisoned anti-corruption blogger Mehman Huseynov, who has refused food for three weeks.

Huseynov, 29, launched his own hunger strike on Dec. 26 after new charges were brought against him that could keep him detained for another seven years.

His supporters include the prominent Azerbaijani investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova, who announced on her Facebook page Monday that she would stop eating and called on the international community to intervene on Heseynov’s behalf. Ismayilova’s own imprisonment between 2015 and 2016 sparked an international outcry.

“I can only sacrifice my time, health and stamina. Please, respond, world,” she wrote.

Daniel Balson, the Europe and Central Asia advocacy director for Amnesty International USA, said the solidarity hunger strike was unprecedented in Azerbaijan.

Corruption and human rights abuses are rife in the southern Caucasus country. President Ilham Aliyev, who succeeded his father in 2003, has abolished term limits and appointed his wife as vice president, drawing accusations that he has effectively established a monarchy in Azerbaijan.

It is estimated that there are currently more than 100 political prisoners in the country, according to Amnesty International USA, and the media is tightly controlled. Last year, the Azerbaijani journalist Afgan Mukhtarli was abducted in the capital of neighboring Georgia and brought to Azerbaijan, where he was sentenced to six years for smuggling and illegally crossing the border.

“All well-known human rights defenders and journalists spend at least one or two years in prison,” said Huseynov’s brother, Emin Huseynov.

He told Foreign Policy that while his brother began his hunger strike by refusing to eat or drink water, he has since begun to drink milk, enabling him to prolong his protest.

Mehman Huseynov ran SANCAQ (“Pin” in Azerbaijani), a popular online magazine across Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. His video reports, which explored government corruption and social problems, frequently garnered hundreds of thousands of views.

In January 2017, plainclothes police officers dragged Huseynov into a van, placed a hood over his head, and took him to a police station, where he was electrocuted and beaten. After he spoke out about the abuse, Huseynov was charged with slander and sentenced to two years in prison for defaming an entire police station.

The blogger was due to be released in March, but new charges that were brought against him, which are widely thought to be politically motivated, could add years to his sentence.

The European Parliament is set to debate a resolution on Thursday calling on Azerbaijan to release all political prisoners unconditionally and to respect the freedom of the press.

The Azerbaijani Embassy in Washington did not respond to a request for comment.

Ismayilova, the investigative journalist, said in the past year that authorities in Azerbaijan have increasingly used this method to tack on extra time to the sentences of political prisoners.

“They’re just giving the message that there is no escape,” she said.

She added that Huseynov’s popularity accounts for the outcry that these new charges have prompted, including among Azerbaijanis not necessarily active in politics.

Azerbaijan has a poor human rights record, but it has not faced the kind of censure or sanctions from the United States that has been imposed on its larger neighbor Russia.

Richard Kauzlarich, who served as U.S. ambassador to Azerbaijan in the 1990s, has called for sanctions to be leveled at Azerbaijani officials under the Global Magnitsky Act, which places travel and financial restrictions on known human rights abusers.

Dozens of individuals across the world are currently sanctioned under the act, which takes its name from a Russian lawyer who died in prison.

Kauzlarich criticized both the Obama and Trump administrations for being reluctant to act on human rights abuses in Azerbaijan.

“Azerbaijanis don’t respond well to private diplomacy. They need to be pressed publicly,”

Kauzlarich said.

A majority Shiite country under secular leadership, Azerbaijan has positioned itself as astrategic partner of the United States and Europe. The country has long been seen as a valuable regional player in the global war on terrorism and is a transit point for U.S. and NATO supplies headed to Afghanistan. The country could also form a crucial part of Europe’s plan to reduce its dependence on Russian energy.

“Washington doesn’t want to compromise other interests,” said Alex Raufoglu, a D.C.-based Azerbaijani journalist.

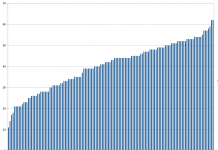

Azerbaijan has been known to lavish Western officials with gifts and foreign trips, in a lobbying strategy that has been dubbed “caviar diplomacy.” The name comes from a 2012 report by the European Stability Initiative, which maintained that Azerbaijan was giving kilograms of caviar to a number of officials from the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, which oversees the implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights. Azerbaijan is one of the council’s 47 member states.

A 2015 investigation by the Washington Post found that in 2013, 10 members of Congress and dozens of their aides were taken on an all-expenses-paid trip funded by the state-run oil company SOCAR to a conference in the capital, Baku, and given lavish gifts, such as silk scarves, crystal tea sets, and Azerbaijani rugs. An ethics report cited by the Post claimed that funds for the trip were channeled through nonprofits in the United States so as to conceal their source.

A letter signed by four political prisoners announcing their hunger strike cautioned other political detainees against waiting for help from the West. “Western organizations have put all principles and values on sale in Azerbaijan,” it read.

The letter could not be independently verified by FP.

“We are overlooked. It hurts. It really hurts,” said Ismayilova, the investigative journalist.

Foreign governments and international organizations welcomed Ismayilova’s release from prison in 2016. But authorities have continued harassing her, and she is banned from leaving the country.

“When I was released, everyone was kind of comforted by this move, and they forgot about the others,” she said.

LINKhttps://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/16/hunger-strike-gains-momentum-in-azerbaijan-political-prisoner-protest-corruption/?fbclid=IwAR2dbclCV2F-ULxHxYT4tSQXE2edEj-GDmonNO5gtJuHinrWyWf7iS-ORsU